The Berkeley Pit

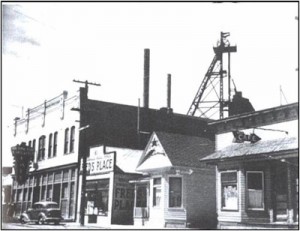

In 1955, mining in Butte saw the light, literally. Excavation on what would become the Berkeley Pit, named from one of several nearby historic underground mines that the Pit would later swallow, began that year in a transition from underground to open pit mining. The Pit would, in the next decade, swallow Butte neighborhoods like Meaderville, Dublin Gulch, and McQueen.

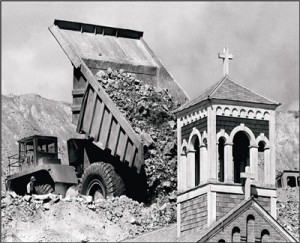

The transition to open pit mining, a highly mechanized form of mining, also meant fewer jobs for the city’s miners. But mining had always been the lifeblood of Butte, and so the community embraced the new mine, and there was little objection to the sacrifice of some of the city’s neighborhoods. While some structures were moved elsewhere, many, like the Holy Savior church, were simply buried.

The Anaconda Company decision to begin open pit mining in Butte was not without its reasons. In 1955, copper prices were the highest they had been since the end of World War I in 1918. And the following year, 1956, would mark the highest copper price seen until 2006 (with the exception of the lone year 1974, when copper briefly spiked due to an end to price controls and the ongoing demands of the Vietnam War). Those high prices gave the Company a big incentive to rethink its Butte operations.

The most accessible parts of the Butte hill had already been mined out. Legend has it that Marcus Daly’s original ore vein was 30% copper. That is extraordinarily rich ore, and the veins of that quality could not last- as a point of comparison, when it opened, the ore mined at the Berkeley was about 0.75% copper, and the ore being mined at Montana Resources Continental Pit operation today is approximately 0.25% copper. In order to economically extract copper from lower grade ore, the Pit was born.

Aside from, and more important than, economic motives, the Pit was also opened because of the simple fact that open pit mining is much less hazardous for the miners themselves. Best guesses put the number of deaths in Butte’s underground mines, which operated for about a century, from the 1860s through 1976, at around 2,500, an average of about 25 deaths per year. Only six fatalities occurred over the life of the Berkeley, which was operated for 27 years from 1955 through 1982. The Continental Pit, which has been mined intermittently since 1980, has seen only one death.

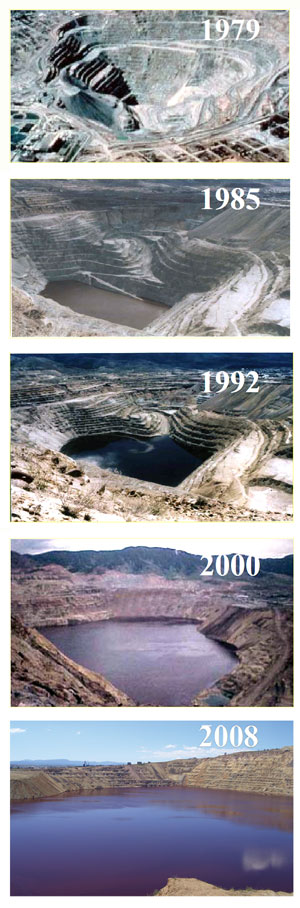

Like the underground mines, the Pit led to unforeseen environmental consequences. Steep, continuous declines in copper prices following the 1974 spike led to the eventual shut down of Berkeley operations in 1982. Throughout the history of mining in Butte, pumps were used to dewater the underground mines and, later, the Berkeley Pit. On April 23, 1982, ARCO, the owners of the former Anaconda Company holdings, announced that they were suspending their Butte operations. Along with the announcement, the underground pumps in the Kelley Mine were shut down. The result: the underground mines and the Berkeley Pit began to fill with acidic water.

Over the active lifespan of the Berkeley, approximately 320 million tons of ore and over 700 million tons of waste rock were mined from the Pit. Put another way, “The Richest Hill on Earth” produced enough copper to pave a four-lane highway four inches thick from Butte to Salt Lake City and 30 miles beyond. Today, the Pit is managed as a federal Superfund site. Plans are in place to monitor water levels to ensure that contamination caused by the Pit does not spread.

For much more on Berkeley Pit history and ongoing management, visit the www.pitwatch.org website.

Click here to return to the main History page

Click here to continue to 1980s: Cleanup Begins