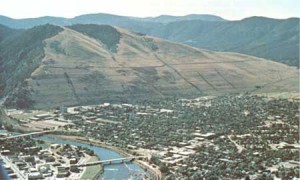

The modern history of the Clark Fork Basin began relatively recently. But that is not the beginning of the Clark Fork story. If we go back far enough, we encounter the unique and somewhat surprising geological history of the basin and western Montana.

Glacial Lake Missoula

The geology of western Montana shaped the landscape we see today. The dominant feature of the area, the Rocky Mountains that form the Continental Divide running roughly north-south through Montana, were formed by geologic and glacial forces. Several fault lines pass through the area, including the Continental Fault that passes through Butte along the base of the East Ridge, a part of the Continental Divide. Western Montana also includes the well-known glacially formed vistas and mountains of Glacier National Park and the geothermal features of Yellowstone National Park.

The scenery of western Montana that we enjoy today was greatly affected by Glacial Lake Missoula, a large lake formed by the expansion and retraction of glaciers during the end of the last ice age, roughly between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago. Glacial ice would cause ice dams, trapping glacial melt and other surface water behind them. Scientists estimate that Glacial Lake Missoula covered 3,000 square miles and contained about half as much water as Lake Michigan.

The lake was primarily caused by ice dams on the Clark Fork River near present-day Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho. Such ice dams caused the valleys of western Montana to flood. Glacial shifts would lead to breaks in the ice dams, which would in turn lead to massive floods that swept across eastern Washington and down the Columbia River Gorge. Current data suggests that there were about 40 such floods over a 2,000 year period. Many of the geologic features of the northwest were created during these floods.

For more about Glacial Lake Missoula, visit the Glacial Lake Missoula website from the Montana Natural History Center; or visit the Glacial Lake Missoula page from the USGS.

Native Peoples in Montana

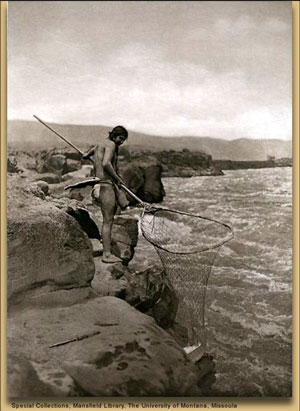

Far before modern civilization came to western Montana, the area was home to a variety of native peoples, including the Bitterroot Salish, the Pend d’Oreille, the Kootenai, the Blackfoot (or Blackfeet), and the Kalispell. The native peoples of Montana lived in ways that sustained the landscape and the people, providing valuable lessons for how we can better preserve the health of our environment today.

The native peoples of Montana were primarily nomadic, traveling to different locations based on the season. Their cultures were based upon longstanding oral traditions and close connections to the natural world. Written records about Montana’s native peoples date back to the Lewis & Clark Expedition in the early 1800s. In 1805, the Salish traded horses to Lewis and Clark. While exploring the Missouri, Lewis and a band of men encountered the Blackfeet. The meeting ended in conflict and the apparent deaths of two Blackfeet warriors.

In 1855, the Salish tribes negotiated the Treaty of Hellgate with the United States government. Translation difficulties and cultural differences resulted in misunderstandings on both sides. Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens sought to obtain the Bitterroot Valley south of modern-day Missoula for the U.S., while the Salish, under Chief Victor, thought they were formalizing their existing friendship with the U.S., and understood that they would not be required to leave their aboriginal lands. Stevens inserted language in the Treaty defining the Bitterroot as a “conditional reservation,” a provision which was almost certainly not made clear to the Salish, particularly considering the translation difficulties.

The Montana gold rush of the 1860s resulted in more pressure on the Salish from encroaching U.S. development. In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant declared that a survey required by the Treaty had found that the Jocko, or Flathead, Reservation to the north was better suited to the needs of the Salish. A Congressional delegation was sent to the area to negotiate the removal of the Salish to the Flathead Reservation. As increased pressure from settlers, combined with the construction of a railroad directly through the tribe’s land without permission or payment, made conditions for the Salish worse, Chief Charlot signed an agreement to leave the Bitterroot in 1889. However, the tribe remained until 1891, when soldiers from Fort Missoula force-marched the tribe 60 miles north to the Flathead Reservation.

The spread of diseases from Europeans, primarily cholera and smallpox, devastated the Blackfoot in the 1800s. Overhunting of buffalo by European hunters caused their numbers to decline, which also seriously impacted the Blackfoot, who depended on the buffalo as a primary food source. Forced to rely on the U.S. government for food, the Blackfoot leader Lame Bull made a treaty with the U.S. in 1855. The U.S. would provide goods and services to the Blackfoot in exchange for their move onto a reservation. In 1860, with supplies from the U.S. government regularly arriving late, the Blackfoot became desperate and raided nearby settlements for food and supplies. In 1870, the U.S. army attacked a peaceful Blackfoot village in retaliation, killing most of that community. In 1874, the U.S. government changed the terms of their treaty with the Blackfoot, moving many of the survivors to Canada, with only the Piegan or Pikuni band allowed to remain in Montana. In the early 1900s, traditional tribal religion and cultural practices were outlawed by the U.S. government. Blackfoot children were forced to attend boarding schools in an attempt to assimilate them into U.S. society.

Learn more about Montana’s Native Peoples at the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes website; at the Blackfoot Nation website; or via Wikipedia’s page on Native American Tribes in Montana.

Lewis & Clark

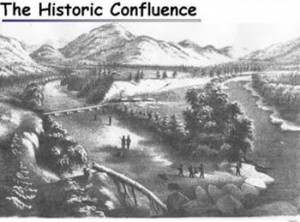

In the course of their expedition to the Pacific Ocean, explorers Lewis and Clark crossed the Continental Divide in 1805 at Lemhi Pass on the Montana-Idaho border west of Missoula. On their return trip in 1806, Lewis explored parts of the Clark Fork Basin, which was later named for William Clark.

Learn more about Lewis & Clark’s journeys through Montana at the interactive Discovering Lewis & Clark website; at the Lewis & Clark Mapping the West website from the Smithsonian; or via Wikipedia’s page on the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Click here to return to the main History page

Click here to continue to 1860s: Gold, Silver and Early Mining