Silver Bow Creek Becomes an Industrial Sewer

The intensive mining and smelting underway in Butte and Anaconda had serious environmental consequences for the entire Upper Clark Fork Basin, consequences that have persisted for over 100 years and that will continue to require

community attention and management for the foreseeable future. By the turn of the 20th century, there were at least a dozen concentrators, smelters and precipitation plants on Silver Bow Creek. William Clark’s Colorado Smelter and Butte Reduction Works were the largest. The City of Butte also discharged its sewage into the creek. The presence of high volumes of mine tailings in the creek led to extensive Acid Rock Drainage (see below).

The amount of waste rock and tailings was immense. For every shovel of rock mined, a tiny bit of copper or other valuable ore is produced. Butte earned the nickname “Richest Hill on Earth” because of the richest veins on the hill, some of which were reportedly more than 30% copper. As a point of comparison, the ore mined today at the Continental Pit in Butte is roughly 0.25-0.35% copper. On average, the ore mined from the Butte hill over the last century is approximately 10% profitable metals (copper, silver, molybdenum). The rest becomes waste, either waste piled at the mine site or the waste from processing, also known as tailings. Because of the tailings’ fine-grained nature, they were exported as waste through Silver Bow Creek in the absence of any environmental laws.

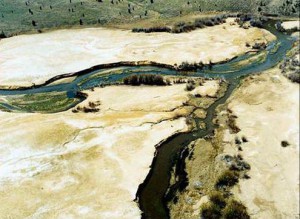

On the floodplain, when the water spread out, it slowed and the tailings dropped out; water without the tailings was allowed to drain back into the channel. This spread tailings across the Silver Bow Creek floodplain in the Butte valley and downstream to the west and north over a large area. As more tailings were flushed downstream, the floodplain deposits would grow thicker.

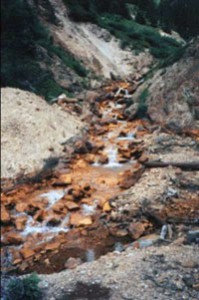

The coarse, granitic rock of the Butte ore body contains substantial amounts of pyrite. The Butte geology is a sulfide ore-body, meaning all of the metals found in the rock are sulfide minerals that can produce sulfuric acid as one of the products of their oxidation when exposed to air and water. Pyrite (iron sulfide), when exposed to air and water, reacts to produce sulfuric acid. Exposed minerals (copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, arsenic, etc.) are dissolved when pH is low (acidic), as in sulfuric acid. The dissolved minerals can be very toxic to fish, bugs, plants and other aquatic life in streams, and can potentially contaminate water supplies used by humans, such as groundwater.

Although this process is often called acid mine drainage, it does not necessarily have to be caused by mining. Any time pyrite is exposed, this process can occur which is why we refer to it as acid rock drainage.

To learn more about Silver Bow Creek, click here to view or download the “Silver Bow Creek: A History of Use, Abuse and Reuse” Powerpoint Presentation.

The Smoke Wars

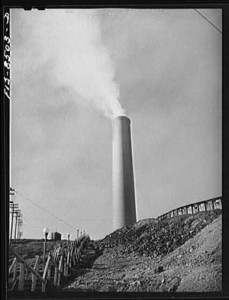

Smelting is the final step in the process where copper concentrate from milling and processing is roasted into pure copper. Airborne byproducts of smelting include arsenic and acidic sulfur fumes. These fumes greatly affected public health; in the worst cases, people experienced bloody noses and vomiting, and sometimes, death. In Butte in the winter months before smelting operations were moved to Anaconda, air inversions would trap smelting pollution in the valley, and Butte death rates were higher than in New York and Chicago.

The fallout from smelting in Butte and, later, Anaconda spread as far north and west as Avon, Montana on the Blackfoot River. These impacts were more intense in the Deer Lodge Valley; Anaconda and its immense smelter sit at the south end of the valley. The northern portion near the town of Deer Lodge has traditionally been more agricultural. When Anaconda smelting was at its peak in the early twentieth century, livestock in the valley were dying routinely and farmers and ranchers could not sell their hay because of high, potentially toxic levels of arsenic.

The book Smoke Wars by Donald MacMillan is an excellent resource on this topic. The following information is excerpted from Smoke Wars: In 1902, in its first year of operation, the Anaconda Stack pumped 30 tons (60,000 pounds) of arsenic trioxide and 150 tons (300,000 pounds) of sulfur dioxide into the air each day. The stack was built to a height of 585 feet in order to further spread and dilute pollution in prevailing air currents. It did nothing to reduce the total volume of pollution. The acidic fumes and resulting fallout caused areas of dead vegetation around Anaconda and in the Deer Lodge Valley.

The farmers and ranchers of the area tried on several occasions to force the Anaconda Company to change its practices through lawsuits. However, the Company was the major industrial force in the state of Montana, and the lawsuits had no practical effect on smelting air pollution.

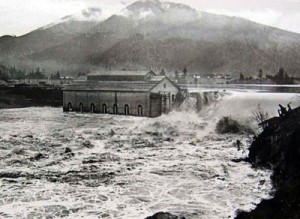

The 1908 Flood

The largest flood on record in the Pacific Northwest came in June of 1908, just months after the Milltown Dam was completed. Plant Superintendent George Slack had said of the Milltown’s construction, “…when the last piece of timber is added to the dam it will be in such condition that the highest waters ever known in this vicinity will not affect it in the least. No expense was spared in making the dam one of strongest of its kind…“

This was somewhat misleading, because there were new dam building technologies available that were better, using primarily concrete and steel, that were being used in other places in Montana, particularly on the Missouri River. Mother Nature called Slack’s bluff. The flood spread the mine tailings concentrated around Butte, Anaconda and Silver Bow Creek down the Clark Fork River. A large volume of tailings settled out against the Milltown Dam just upstream from Missoula. Workers dynamited the dam spillway to prevent the force of the flood from washing out the spillway and powerhouse. Butte and the rest of the Clark Fork were stricken with major environmental damage that has affected the health of our watershed for the last 100 years.

The 1908 flood was just as devastating to the rest of the basin. Mine waste settled in the upper Clark Fork River floodplain between Warm Springs and Garrison. There are roughly 1,000 acres of barren, tailings-contaminated areas in this section of the Clark Fork, called “slickens” by the Deer Lodge Valley ranchers because of the areas’ lack of vegetation and “slick” quality when wet. Silver Bow Creek itself was impacted more heavily. All 22 miles of the floodplain between Butte and Warm Springs is currently being replaced through remediation and restoration work.

Nearly 6 million cubic yards of mine waste impacted nearly 1,500 acres of land through the flood and the tailings it carried downstream. Cleanup of Silver Bow Creek alone, when all is said and done, will bear a price tag of roughly $80 million. At Garrison, the Little Blackfoot River joins the Clark Fork, doubling the flow. Also, the floodplain narrows as the Clark Fork enters a series of canyons en route to Missoula. These two factors made it possible for the river to carry all of the remaining tailings in the stream 120 miles downstream to where most of the contamination would stop and settle behind the Milltown Dam.

To learn more about the 1908 flood, click here to view or download the “Centennial of the Clark Fork’s Great Flood” PowerPoint Presentation.

Click here to return to the main History page

Click here to continue to 1955: The Open Pit Mine Era